Faces in plane

I took a Geometric Algorithms course in which we learned various common techniques used in designing algorithms for geometric problems. In this course we also had to make a simple game using some geometric algorithms in small groups. The game itself wasn't very interesting or worth mentioning, but it did require me to come up with an interesting algorithm, which I implemented here in TypeScript.

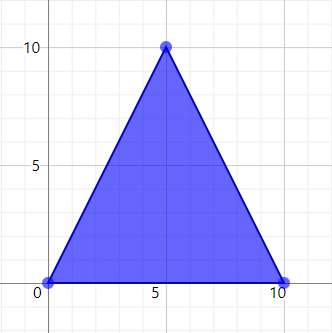

This algorithm takes a set of simple polygons as an input. Simple polygons are shapes constructed from a list of points, where the boundary consists of the chain of segments between consecutive points (and the first and last point). Simple polygons additionally don't allow any of these segments to intersect. For instance the point list [{x: 0, y: 0}, {x: 10, y: 0}, {x: 5, y: 10}] describes a simple triangle polygon:

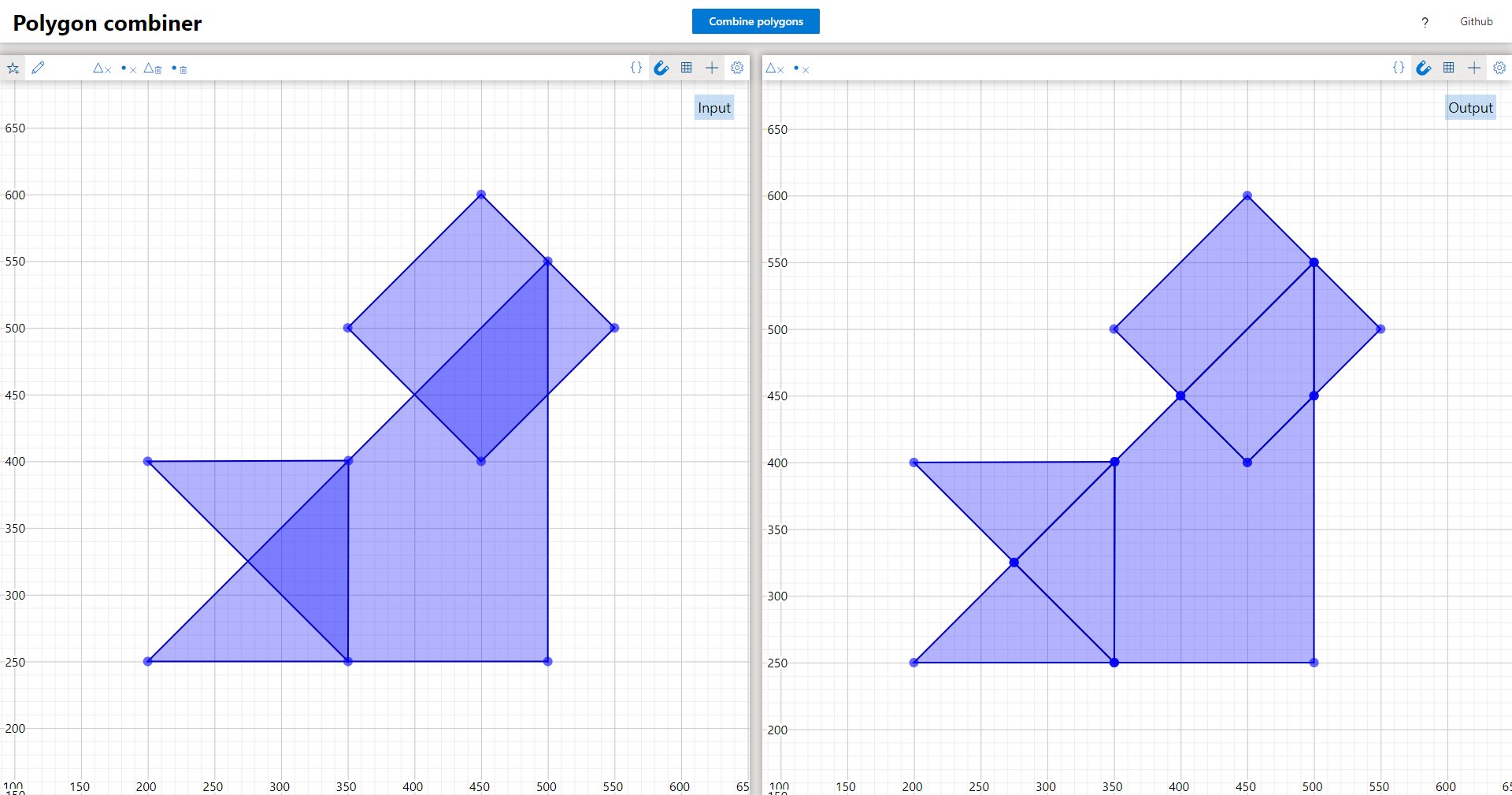

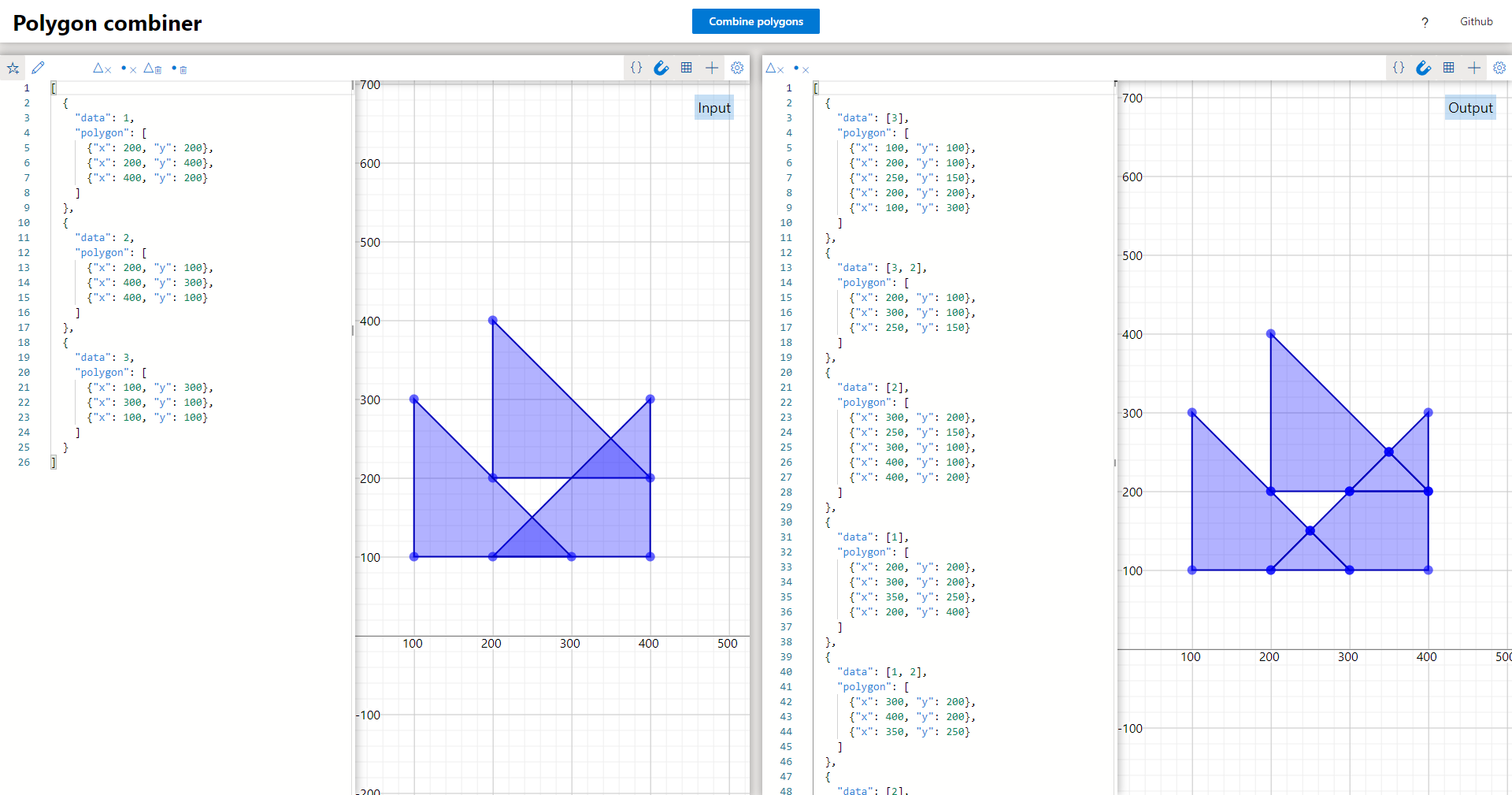

The algorithm then combines all of these polygons by projecting them on the same plane, and seeing what faces (areas) are formed (based on how the polygons intersect each other). These faces are also described by simple polygons in the output. In the implementation of my algorithm I allow additional data to be attached to polygons. This data is used in the output polygons to encode the input polygons that overlap with this face.

The goal of the algorithm is essentially to take a set of overlapping polygons, and produce a set of equivalent non-overlapping polygons, in a way that no information is lost.

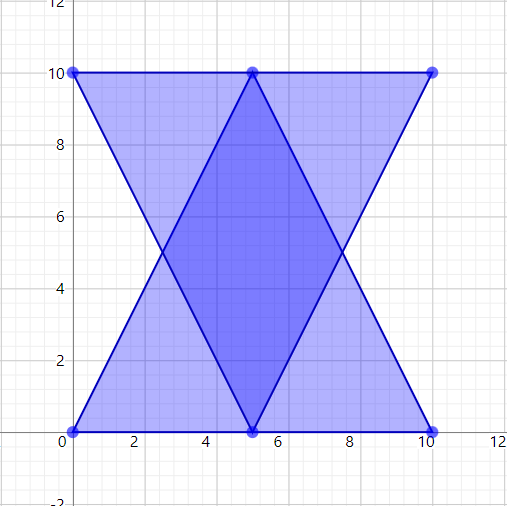

Consider for instance the following input consisting of two triangles:

const polygon1 = {

data: 1,

polygon: [

{x: 0, y: 0},

{x: 10, y: 0},

{x: 5, y: 10},

],

};

const polygon2 = {

data: 2,

polygon: [

{x: 0, y: 10},

{x: 10, y: 10},

{x: 5, y: 0},

],

};

const input = [polygon1, polygon2];which is drawn as:

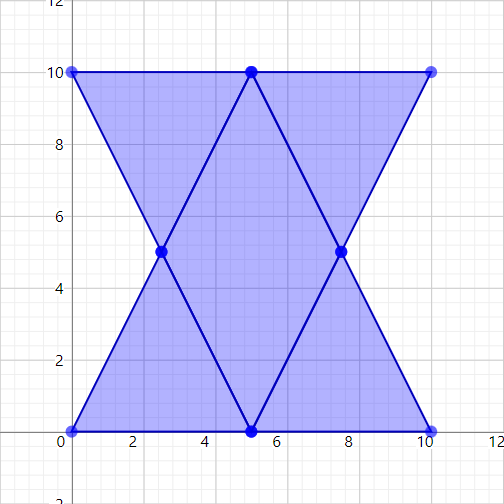

When running the algorithm on this input, 5 independent faces will be found, and each face will specify what polygons it was constructed from:

View code

const output = [

{

data: [polygon1],

polygon: [

{x: 0, y: 0},

{x: 5, y: 0},

{x: 2.5, y: 5},

],

},

{

data: [polygon1, polygon2],

polygon: [

{x: 2.5, y: 5},

{x: 5, y: 0},

{x: 7.5, y: 5},

{x: 5, y: 10},

],

},

{

data: [polygon1],

polygon: [

{x: 5, y: 0},

{x: 10, y: 0},

{x: 7.5, y: 5},

],

},

{

data: [polygon2],

polygon: [

{x: 0, y: 10},

{x: 2.5, y: 5},

{x: 5, y: 10},

],

},

{

data: [polygon2],

polygon: [

{x: 5, y: 10},

{x: 7.5, y: 5},

{x: 10, y: 10},

],

},

];which is drawn as:

Algorithm

Given an input with a total of n vertices (points of polygons) where the algorithm produces an output consisting of k polygons, the algorithm can run in O((n + k) * log n)time. My specific implementation in TypeScript is slightly less efficient though, and given a maximum of s overlapping polygons in the input, runs in O((n + k) * (s + log n)) time.

I will glans over some basic aspects of the algorithm here, but it's described in more detail in algorithm.pdf. The algorithm is based on the sweep-line technique. This is a technique where the algorithm sweeps a virtual scan-line across the plane, and builds up the output when relevant points are passed. An example of this is illustrated in the gif below (taken from wikipedia) that shows-off Fortunes-algorithm for computing voronoi-diagrams:

Note however that this sweep line doesn't really go through all possible positions on a plane, since there's an infinite number of these. One could do an approximation and take an arbitrary step size to move the sweep line by to ensure there's only a finite number of steps to consider, but this would lead to inaccurate results. We can do much better, decreasing the number of positions to consider while increasing the precision: we simply only consider event points. These event points define the coordinates at which interesting things occur, and our data has to be updated.

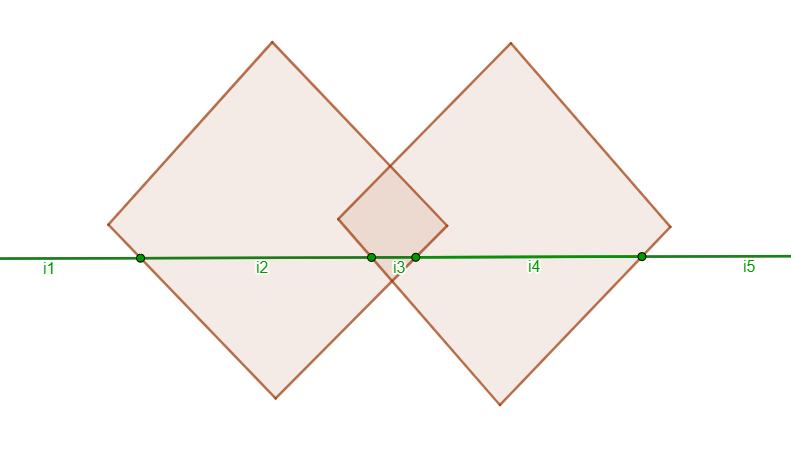

My algorithm performs a vertical sweep of the plane, and keeps track of the different intervals formed by polygons on the scan-line. Below is an image showing two diamond polygons and a green scan-line:

The algorithm tracks these discrete regions formed on the scanline: i1, i2, i3, i4, and i5. For each of these regions it will store what the left and right boundary segments are (if any), and the set of polygons that are in this region. For instance regions i1 and i5 only have a single boundary each and contain no polygons. Regions i2 and i4 have 2 boundaries each, and each contain one of the diamond polygons. Lastly region i3 has 2 boundaries and contains both diamond polygons.

In this image the sweep-line is drawn at a random position, but in reality this drawn position is never considered. We're only interested in maintaining an accurate representation of the information above, meaning we only have to consider points at which this information changes. This happens at any corner of any polygon in the input, as well as any intersection of segments. These event points are stored in a sorted queue, such that we can easily extract what the next event is that will occur. Each of the polygons' corners are thrown in this queue at the start of the algorithm, and any intersections are computed as the scan-line is moving. When a region is added or removed from the scan-line, any nearby regions are checked for whether their boundaries might intersect in the future, and such event points are added to the queue. This way we don't have to check for intersection between all segments in the input (a quadratic number), but only have to consider segments that have a real chance of intersecting.

While this sweep is occurring, relevant data about the regions is also stored in a separate data structure. After executing the entire sweep, this data is used to reconstruct all faces that were encountered.

Everything is a little more nuanced than described here, but this captures the basic idea behind the algorithm. The algorithm for instance also has to deal with many edge cases that occur when polygons have corners at the same y-coordinates, or even when multiple polygons share the exact same corners. These edge cases have been considered before working out the algorithm, and it seems to handle them well. Problems however still occur when a point lies on the boundary of another polygon. This is caused by rounding errors, where one part in the algorithm may think the point lies left of the boundary and another part thinks it lies right of it, where as in reality it lies exactly on it. These types of problems are known as robustness issues, and I couldn't solve them for my algorithm despite my best effort. I also didn't consider such possible issues well enough in the initial designing phase, and instead only considered them after having encountered them in practice with my TypeScript implementation.

Demo

An implementation of the algorithm can be found at github.com/TarVK/faces-in-plane. The algorithm is also accompanied by a demo webpage, at which the algorithm can be tested: tarvk.github.io/faces-in-plane/demo.

For this demo site I made the polygon editor from scratch, sine I couldn't find any existing library for this that looked decent. This editor makes use of SVGs for drawing the polygons. I also made a way of directly editing and viewing the text representation of the polygons:

In this demo the data field of the output contains the concatenation of the data of the source polygons at this face, rather than the whole source polygon. This was done to keep the output data more readable and less cluttered. Part of the code for this editor has also been reused in Sweeper since I needed a 2d shape editor here too.