Model checker

There are many things in the world that can be considered in terms of "behavior": Software processes, business processes, board games, etcetera. This behavior can be formally described in many ways, one of which is the Labeled Transition System (LTS). Once behavior is formally modeled, desirable properties can also be modeled. Modal mu calculus is one such formalism to describe properties. The act of model checking is verifying whether these properties are met by the described behavior.

Labeled Transition Systems

A LTS formally consists of 3 parts:

- A set of nodes/states

- A set of labels/actions

- A transition relation mapping nodes to another using labels

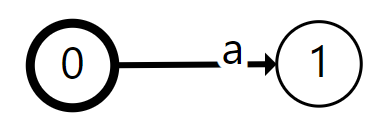

All these parts are commonly represented in a simple to understand drawing. Consider for instance a LTS consisting of:

- 2 states:

0and1 - One label:

a - One transition, connecting

0to1by means ofa

This LTS can be drawn as follows:

Usually an initial state is identified on the LTS, and for instance drawn with a thicker border like above. This LTS describes the behavior that a single a action can occur, and nothing else can happen afterwards.

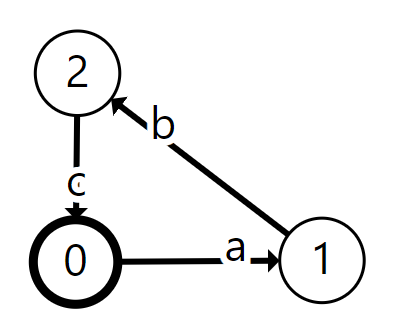

LTSes can describe infinite behavior, by means of loops. Consider for instance the following LTS:

Here we start in state 0 again, and we can follow the transition arrows in a loop. Thus this behavior describes the infinite sequence of a, b, c being iterated.

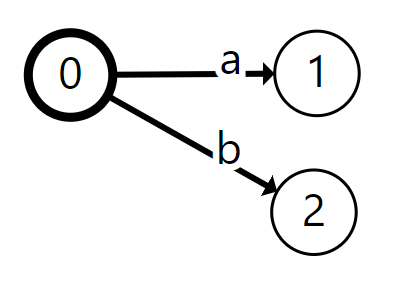

Finally LTSes can describe non-deterministic behavior. In other words, we don't know what will happen, multiple routes can be taken:

These actions are rather abstract - and can represent almost anything depending on what you're modelling, so we will have a look at an example to get a better intuition.

Also note that describing behavior with an LTS by hand is often a lot of effort since LTSes can become very large when encoding all possibilities. Certain behavior even requires infinitely large LTSes to fully describe the behavior. For this reason most real world modelling systems use LTSes as an underlying mathematical model, but build a higher level and more user friendly modelling formalism on top of this. This model could then be translated to an (possibly infinite) LTS. One example of such a higher-level formalism is that of Petri nets, and another is mCRL2's process-algebra.

Modal Mu-calculus

When we have a model to be checked, modal mu-calculus (μ-calculus) formulas can be written and verified on the model.

One can create a formula according to the following CFG:

f,g ::= false | true | (f) | !f | f && g | f || g | f => g | [r]f | <r>f | mu X.f | nu X.f | X

r,s ::= A | (r) | r + s | r . s | r* | r+

A,B ::= false | true | a | (A) | !A | A && B | A || B

Here a ranges over all actions present in your LTS, and X ranges over all valid variable names. Informally, the semantics of each of the base formula constructs can be explained in terms of (not) including a state s of an LTS as follows:

false: never includes statestrue: always includes states(f): includes statesiffincludes states!f: includes statesiffdoes not include statesf && g: includes statesiffincludes statesandgincludes statesf || g: includes statesiffincludes statesorgincludes statesf => g: includes statesif wheneverfincludes states,galso includes states[r]f: includes statesif for every path according torfromsto some stateq,fincludes stateq<r>f: includes statesif there exists some path according torfromsto some stateqwherefincludes stateqmu X.f: includes statesif formulafincludess, where only a finite sequence ofXvariables was usednu X.f: includes statesif formulafincludess, where possibly an infinite sequence ofXvariables is usedX: includes statesif the fixed point (muornu) that binds the variableXincludess

Next we have to express what paths an expression r represents. We informally define whether an expression r includes path p for each construct:

A: includespifpconsists of a single action, which is contained in setA(r): includespifrincludespr + s: includespifrincludesporsincludespr . s: includespifrincludes a start sub-path ofp, andsincludes the remainder of the path ofpr*: includespifpcan be split into 0 or more sub-paths that each are included inrr+: includespifpcan be split into 1 or more sub-paths that each are included inr

Finally we have to express whether an action ac is present in a set of actions:

false: never includesactrue: always includesac(if it appears somewhere in the LTS)a: includesacifac == a(A): includesacifAincludesac!A: includesacifAdoes not includeacA && B: includesacifAincludesacandBincludesacA || B: includesacifAincludesacorBincludesac

Using this syntax we can express properties of the LTS rather concisely. For instance a formula describing that there exists a path of a and b transition labels leading to a state with only c transitions can be described as follows:

<(a||b)*>!<!c>trueThis reads as: there exists a path of a or b transitions repeated 0 or more times to a state where there does not exist an outgoing transition that's not a c transition to any other state.

A more extensive description of these formulas as well as more extensive formulas not supported by my model checker can be found here on mCRL2's website.

Model checking example

Using model-checking, we can check whether the game of tic-tac-toe games has a winning strategy. A winning strategy is strategy such that no matter what choices the opponent makes, you're guaranteed to win (when playing according to the strategy).

Our model will have to describe all possible games of tic-tac-toe that can be played. Fortunately for us, tic-tac-toe is such a simple game that this is still quite computable.

Generating the LTS

Creating a LTS by hand is usually rather cumbersome, since they can easily become extremely large. We shall use some JavaScript code to generate a LTS representing all possible tic-tac-toe games.

In our code, we shall represent the game by a 9 value long list, containing either the token "o", "x", or null:

const emptyGame = new Array(9).fill(null);The indices correspond to grid values as follows:

| 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6 | 7 | 8 |

Each of these states can also be encoded as a single number by representing each token with a digit, and giving each token its own index in base 3. We also add an extra dedicated state to represent the game being finished:

const stateID = game =>

game.reduceRight((s, v, i) => s + {null: 0, x: 1, o: 2}[v] * 3 ** i, 0);

const finishedID = 3 ** 9;Next we create some functions to retrieve the indices of remaining cells in which a player can still put their cross or nought, and a function to get a new game by putting a cross or nought at a given index:

const remaining = game => game.flatMap((v, i) => (v == null ? [i] : []));

const set = (game, i, player) => [

...game.slice(0, i),

player,

...game.slice(i + 1),

];Given a game state, we would also like to know whether either of the players have won. There are 3 different options we have to consider there:

- 3 tokens of the same type in a row

- 3 tokens of the same type in a column

- 3 tokens of the same type on a diagonal We can check this using the following code:

const getIndex = (i, j) => i + j * 3;

const won = (game, player) => {

for (let i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

const wonColumn = [0, 1, 2].every(j => game[getIndex(i, j)] == player);

const wonRow = [0, 1, 2].every(j => game[getIndex(j, i)] == player);

if (wonColumn || wonRow) return true;

}

const wonDiagonal1 = [0, 1, 2].every(i => game[getIndex(i, i)] == player);

const wonDiagonal2 = [0, 1, 2].every(

i => game[getIndex(2 - i, i)] == player

);

return wonDiagonal1 || wonDiagonal2;

};Finally we obtain all possible transitions from one state to another, starting at the state of an empty game. Each transition is encoded as a tuple: [fromStateID, label, toStateID]. Strings are used to label each transition, where x4 means the cross player placed an x at index 4, and x-won to represent player x won. Similar labels exist for the other player, and all other indices. The resulting code looks as follows:

const opposite = player => ({x: "o", o: "x"}[player]);

const getTransitions = (game, player, visited = new Set(), out = []) => {

const ID = stateID(game);

if (visited.has(ID)) return;

visited.add(ID);

if (won(game, "x")) out.push([ID, "x-won", finishedID]);

else if (won(game, "o")) out.push([ID, "o-won", finishedID]);

else

remaining(game).forEach(i => {

const newGame = set(game, i, player);

out.push([ID, player + i, stateID(newGame)]);

getTransitions(newGame, opposite(player), visited, out);

});

return out;

};These transitions can then be transformed into an LTS in Aldebran format which our model-checker can read in:

const getLTS = transitions =>

`des(0, ${transitions.length}, ${finishedID})\n` +

transitions

.map(([from, action, to]) => `(${from}, "${action}", ${to})`)

.join("\n");

copy(getLTS(getTransitions(emptyGame, "x")));Now executing this code stores a LTS in our clipboard, representing all possible tic-tac-toe games in which cross plays first. Below is the code as a whole:

View code

const emptyGame = new Array(9).fill(null);

const stateID = game =>

game.reduceRight((s, v, i) => s + {null: 0, x: 1, o: 2}[v] * 3 ** i, 0);

const finishedID = 3 ** 9;

const remaining = game => game.flatMap((v, i) => (v == null ? [i] : []));

const set = (game, i, player) => [

...game.slice(0, i),

player,

...game.slice(i + 1),

];

const getIndex = (i, j) => i + j * 3;

const won = (game, player) => {

for (let i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

const wonColumn = [0, 1, 2].every(j => game[getIndex(i, j)] == player);

const wonRow = [0, 1, 2].every(j => game[getIndex(j, i)] == player);

if (wonColumn || wonRow) return true;

}

const wonDiagonal1 = [0, 1, 2].every(i => game[getIndex(i, i)] == player);

const wonDiagonal2 = [0, 1, 2].every(

i => game[getIndex(2 - i, i)] == player

);

return wonDiagonal1 || wonDiagonal2;

};

const opposite = player => ({x: "o", o: "x"}[player]);

const getTransitions = (game, player, visited = new Set(), out = []) => {

const ID = stateID(game);

if (visited.has(ID)) return;

visited.add(ID);

if (won(game, "x")) out.push([ID, "x-won", finishedID]);

else if (won(game, "o")) out.push([ID, "o-won", finishedID]);

else

remaining(game).forEach(i => {

const newGame = set(game, i, player);

out.push([ID, player + i, stateID(newGame)]);

getTransitions(newGame, opposite(player), visited, out);

});

return out;

};

const getLTS = transitions =>

`des(0, ${transitions.length}, ${finishedID})\n` +

transitions

.map(([from, action, to]) => `(${from}, "${action}", ${to})`)

.join("\n");

copy(getLTS(getTransitions(emptyGame, "x")));The output of the code can be found here, but you can also execute it in your browser's JavaScript console.

Verifying formulas

We can now use mu-calculus to ask questions about our model. The model encodes that cross always makes the first move. It would be interesting to know whether nought can win at all if cross begins. You probably already knows this is definitely possible, but we can also verify this formally with our model.

We use the minimal fixed point operator mu, which essentially allows us to define a recursive formula. We shall let X represent the states in which player nought can win. We say that player nought can win the game either if:

- There exists a

o-wontransition (remember that's how we encoded a winning state in our model) - There exists a transition of a move made by cross (

x0-x8) to a state where nought can win - There exists a transition of a move made by nought (

o0-o8) to a state where nought can win

All with all, the formula is expressed as follows:

mu X. (

<o-won>true

|| <x0+x1+x2+x3+x4+x5+x6+x7+x8>X

|| <o0+o1+o2+o3+o4+o5+o6+o7+o8>X

)

When running this in a model-checker, we will see that the formula is satisfied by the LTS, and hence player nought can indeed win.

Now we would like to know whether nought also have a strategy that ensures they win. We can transform our previous formula to represent this, by replacing the statement:

- There exists a transition of a move made by cross (

x0-x8) to a state where nought can win

By the following statement:

- For all transitions of a move made by cross (

x0-x8) to a states, nought can wins

We have to be careful here though, because nought and cross alternate in making moves. Hence for some states cross has no transitions at all, in which case this condition is trivially met. If cross has no transitions, then for all transitions it does have (none) nought can win. Hence we have to additionally add the following condition to this:

- And cross has at least a single transition of a move they can make (

x0-x8)

The formula representing this looks as follows:

mu X. (

<o-won>true

|| (

<x0+x1+x2+x3+x4+x5+x6+x7+x8>true

&& [x0+x1+x2+x3+x4+x5+x6+x7+x8]X

)

|| <o0+o1+o2+o3+o4+o5+o6+o7+o8>X

)

Trying to verify this in any model checker will now tell us that this formula is not satisfied by the model. Hence nought has no winning strategy for the game if cross makes the first move.

Symmetrically we can check whether cross has a winning strategy in that case:

mu X. (

<x-won>true

|| (

<o0+o1+o2+o3+o4+o5+o6+o7+o8>true

&& [o0+o1+o2+o3+o4+o5+o6+o7+o8]X

)

|| <x0+x1+x2+x3+x4+x5+x6+x7+x8>X

)

This property is however also not met. Neither cross or nought has a strategy that guarantees they win.

Logically, this must then mean that if neither cross nor nought can force a win, they must both be able to at least force a draw. I.e. there should exist a strategy that guarantees that the player does not lose.

We can check whether nought has such a strategy with a formula constructed using the maximal fixed point operator nu. The construction is quite similar to our previous one. X represents the states in which there is a strategy to not lose, it consists of 3 parts:

- There does not exist

x-wontransition from this state - And for all moves cross can make, nought has a non-losing strategy

- And there exists a move nought can make to a state in which they have a non-losing strategy, or nought can't make a move at all in this state

nu X. (

!<x-won>true

&& [x0+x1+x2+x3+x4+x5+x6+x7+x8]X

&& (

<o0+o1+o2+o3+o4+o5+o6+o7+o8>X

|| !<o0+o1+o2+o3+o4+o5+o6+o7+o8>true

)

)

A model-checker will tell us that this property is indeed met by the model, and the symmetric property of cross having a non-losing strategy is also met:

nu X. (

!<o-won>true

&& [o0+o1+o2+o3+o4+o5+o6+o7+o8]X

&& (

<x0+x1+x2+x3+x4+x5+x6+x7+x8>X

|| !<x0+x1+x2+x3+x4+x5+x6+x7+x8>true

)

)

Hence in the game of tic-tac-toe, no strategy exists that can guarantee a win, but at least a strategy exists that can guarantee you don't lose.

Implementation

For the Algorithms for model checking (2IMF35) course taught at the TU/e, I created a simple model-checker from scratch. It was written in TypeScript, and a surrounding website was build around it using React, Fluent-UI and Monaco.

The model-checker is presented as a web-tool here, and the code can be found here.

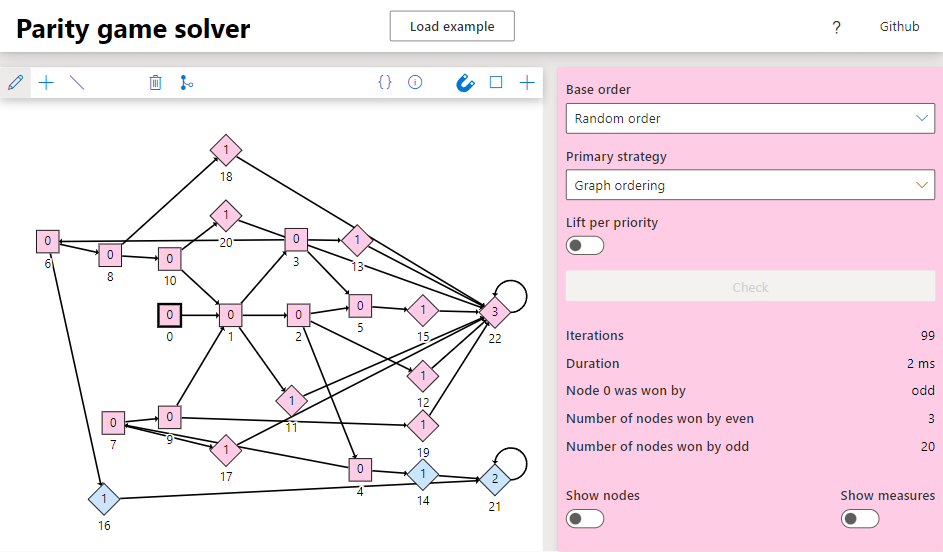

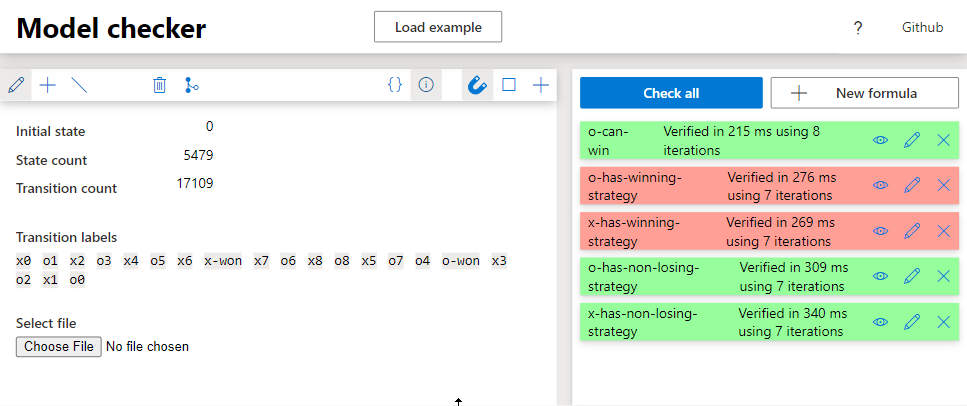

Below is an image showing the results of model checking problem described in the previous section:

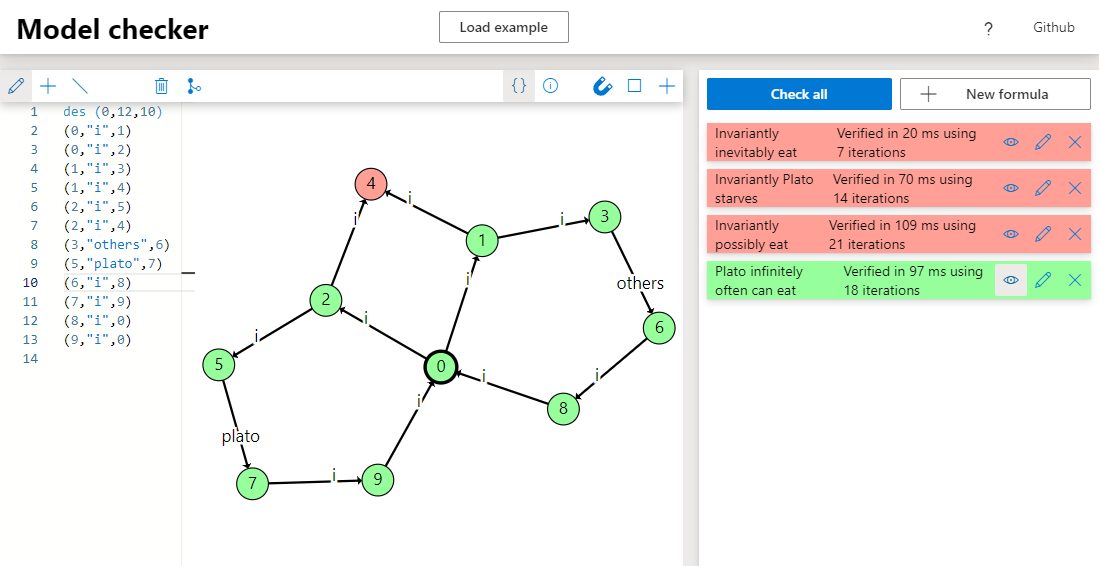

This model is too large to graphically visualize, but for smaller models the LTS can be viewed graphically:

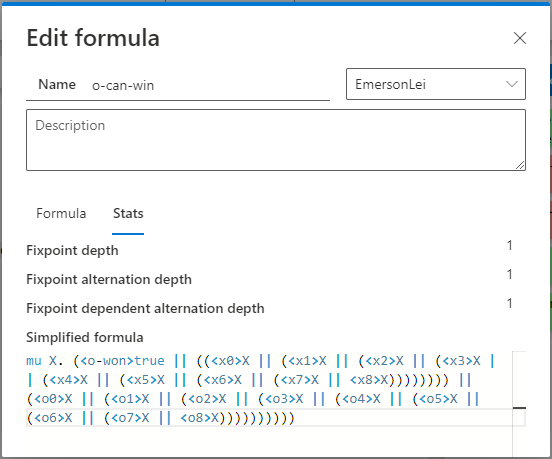

The course requested us to verify mu-calculus formulas in the following format:

f,g ::= false | true | (f && g) | (f || g) | [a]f | <a>f | mu X.f | nu X.f | XHere a ranges over all actions present in your LTS, and X ranges over all valid variable names.

Hence there is no implication, brackets are fixed around conjunction and disjunction, and there are no action formulas. In order to fully comply with the assignment (and as a fun challenge) I added the syntax described previously on top of the base syntax, but perform model-checking only on formulas written in the base syntax. This advanced syntax turns out to not increase expressiveness of the formulas, but only helps to make them a bit smaller and or easier to read. Therefor my program is able to transform any formula written with the more advanced syntax into a formula written in this base syntax. These transformed formulas can be found under the stats tab when editing a formula:

For example the formula:

nu X. (

!<x-won>true

&& [x0+x1+x2+x3+x4+x5+x6+x7+x8]X

&& (

<o0+o1+o2+o3+o4+o5+o6+o7+o8>X

|| !<o0+o1+o2+o3+o4+o5+o6+o7+o8>true

)

)

Is transformed into this:

nu X. ([x-won]false && (([x0]X && ([x1]X && ([x2]X && ([x3]X && ([x4]X && ([x5]X && ([x6]X && ([x7]X && [x8]X)))))))) && ((<o0>X || (<o1>X || (<o2>X || (<o3>X || (<o4>X || (<o5>X || (<o6>X || (<o7>X || <o8>X)))))))) || ([o0]false && ([o1]false && ([o2]false && ([o3]false && ([o4]false && ([o5]false && ([o6]false && ([o7]false && [o8]false)))))))))))Due to lack of formatting and excessive brackets this formula is much harder to read currently, but besides this you can also clearly see that it has more characters in total. Certain families of formulas (depending on the LTS) will be exponentially larger in this simplified form. Semantically these formulas will always be entirely equivalent however, allowing us to do model-checking on this form instead.

The model-checker can both use a naive recursive algorithm to compute the set of states for which a formula is satisfied, and use the Emerson-lei algorithm for this.

Parity game solving

Instead of using a simple recursive algorithm to compute the states that satisfy a formula, one can also solve a parity game. The concept of parity games is quite a few abstractions removed from the intuitive idea of model-checking, but is useful in practice.

To use parity games for model checking, the LTS and mu-calculus formula are first combined into a single Boolean Equation System (BES). Each state in the LTS has a corresponding variable in the equation system such that given a solution to the equation system, we can also determine whether a given state satisfies the mu-calculus formula. Next, this BES can be translated to a parity game, such that the solution to the parity game trivially yields a solution to the BES as well.

Both BES and parity games have some freedom in how solutions are found, and hence heuristics can be used to speed up the process of model-checking.

Parity games

A minimum parity game is represented by a graph, where each node has two attributes:

- An owner: Either

EvenorOddrepresented by a diamond and square shape respectively - A priority: A number shown in the node itself

Additionally, each node in the graph must have at least one outgoing edge for it to be a valid parity game. We may also show the identifier/name below the node, but this has no real effect on the game.

To play the game, a token is placed on one of the nodes. The owner of the node can decide to move the token to one of the successor nodes. Since each node has at least one outgoing edge this process can continue indefinitely. Because the parity game itself is only finite, this means that certain nodes must be visited infinitely often. Between all nodes that are visited infinitely often, we consider the one with the lowest priority. If this priority is even, player Even wins the game, otherwise player Odd wins the game.

For both player Even and player Odd an optimal strategy exists. A parity game solver can determine what player wins the game when the token starts in a certain node, assuming both players play optimally.

Parity game solver implementation

The second assignment for the Algorithms for model checking course asked us to implement the Small Progress Measures Algorithm to solve parity games.

This algorithm describes an approach that always results in a correct output. It however leaves open certain details which can greatly affect the speed of the algorithm in the real world. The algorithm tells us to "Lift a node" as long as there's a node for which lifting changes the state, without describing what node to lift when there are multiple nodes that can successfully be lifted. Nor does it describe how to find a node that can be lifted successfully. My implementation provides several approaches to pick such a node, in terms of the following attributes:

- The base order to check nodes in

- A strategy of how to deviate from this base order

- Whether lifting should be grouped by priority

These attributes can be combined in different ways. Which approach is most effective depends on the parity game at hand. The default configuration which uses the graph ordering strategy and does not lift per priority seems most generally effective.

Approach options

Base orderings:

- Input order: Follows the order in which the nodes are defined in the textual representation

- Random order: Randomly shuffles the order of the nodes according to a fixed seed

- Priority order: Sorts the nodes from highest to lowest priority

- Graph order: Sorts the nodes according to predecessor vertices, in an attempt to have more consecutive lifts enabled

- Gain order: Sorts nodes in a lexicographical ordering of 3 aspects to maximize the possible gain to be made: odd priority first, odd owner first, lower priority first

Strategies:

- Direct cycle: Simply iteratively goes through the base order, until none of the nodes are successfully lifted

- Repeat nodes: Goes iteratively through the base order, but lifts each node repeatedly until it can no longer be lifted (handles self loops well)

- Adaptive ordering: Goes iteratively through the base order, but whenever lifting fails, the node is moved to the back of the list and the cycle restarts from the beginning of the list

- Graph ordering: Goes iteratively through the base order. Whenever lifting is successful, a breath for search is performed on all nodes that lift successfully using the predecessor relation. Whenever this search detects a cycle that was successfully lifted,this cycle repeats until it can no longer be lifted successfully

Grouping:

- No grouping: The selected strategy is applied on an ordering involving all nodes at once

- Lift per priority: The graph is partitioned into clusters of the same priority, and the selected strategy and ordering is applied per cluster. The lifting happens from highest to lowest priority and loops around until no progress can be made anymore. Each cluster repeats lifting within its cluster, until no progress is made within the cluster anymore.

The website for the first assignment was modified to also provide a visual interface for this project. This web-app can be accessed here, and the source code can be found here.

Below is an image of the web-app: